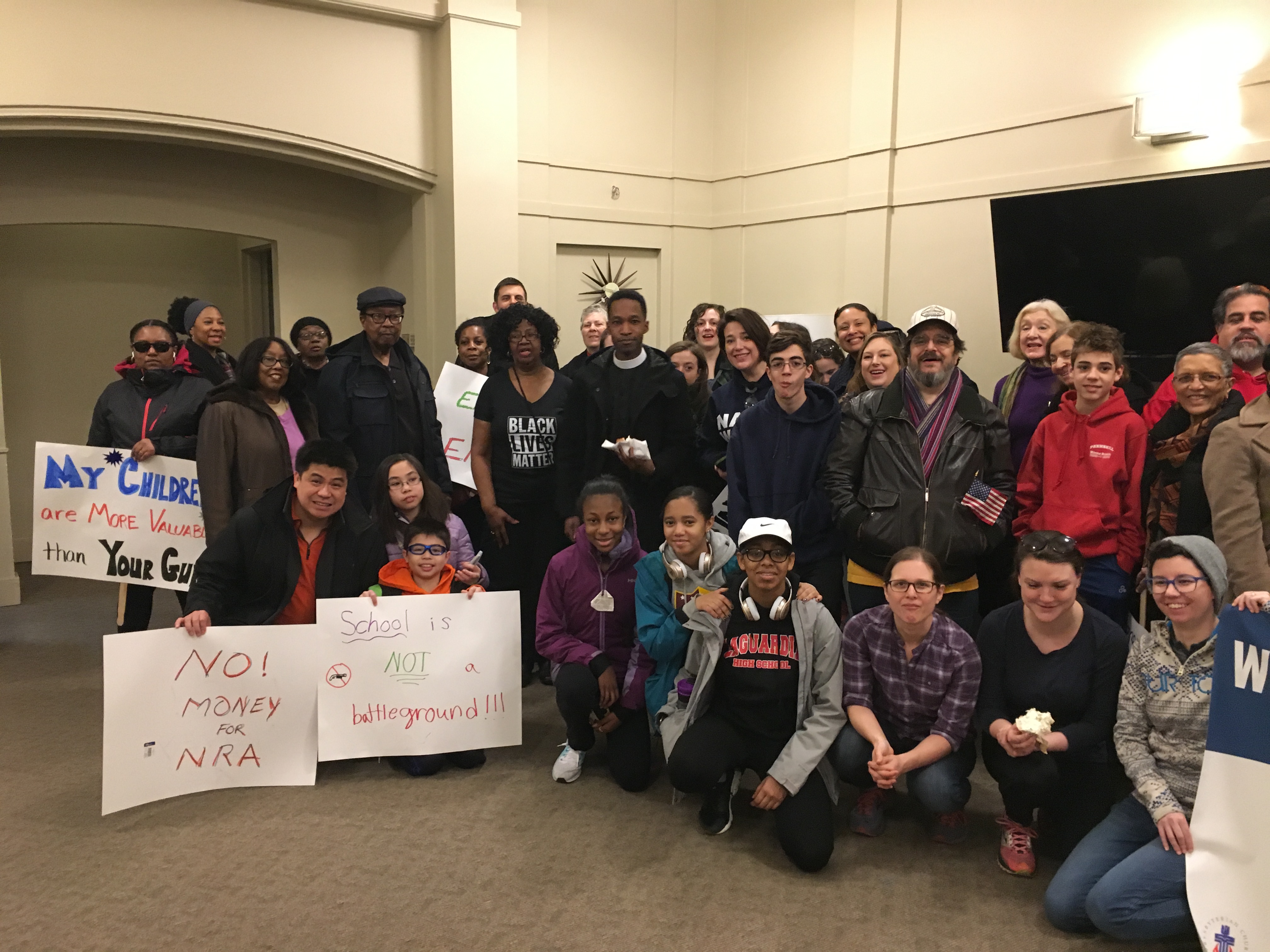

At the Presbytery of New York City’s annual commemoration of Mrs. Rosa Parks and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., held on January 21, 2019 at Eastchester Presbyterian Church, I had the privilege of speaking to the Letter from Birmingham City Jail. These are the words I took into the lectern; they are close to what I said.

November 1962. Birmingham, Alabama.

An election changed the city’s form of government from three elected commissioners to a mayor and city council.

April 2, 1963. Birmingham, Alabama.

In Birmingham’s first mayoral election, Albert Boutwell defeated Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s Commissioner of Public Safety who had oversight of the fire and police department in a close election. Connor attributed his defeat to the small number of African-American voters who he said voted for his opponent’s more moderate stance.[i] Due to a lawsuit about the change of government, Connor remained as Commissioner of Public Safety until May 1963.

April 3, 1963. Birmingham, Alabama.

Recognizing that a more moderate stance was simply a more refined version of the segregationist policies sustaining the Jim Crow status quo, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, led by the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., began coordinated nonviolent actions against the city’s practices of racial discrimination.[ii] The campaign included sit-ins, marches, boycotts of businesses, and a voter registration drive.[iii]

April 10, 1963. Birmingham, Alabama.

Commissioner Connor obtained an injunction banning nonviolent protests.[iv]

April 12, 1963. Birmingham, Alabama. Good Friday.

After a period of intense discernment, conversation, and prayer, fifty individuals violated the injunction and were arrested. Among them were the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.[v]

That same day, eight white clergymen from Alabama published “A Call for Unity” that read in part:

[W]e are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.[vi]

April 12 – 20, 1963. Birmingham City Jail.

The Rev. Dr. King, Jr. was held in the jail. At some point, he saw a newspaper containing “A Call for Unity.” He began to write a response in longhand in the newspaper margins. His wrote on scraps of paper provided by a friendly black trusty. He finished on a pad provided by his attorneys.[vii]

This document which we now know as the Letter from Birmingham City Jail combines social and political analysis with theological insights and a clarion prophetic call to speak to the concerns of the white clergymen and to illustrate that the Birmingham Campaign was just and loving, rooted in faith, wise and timely.

The Rev. Dr. King, Jr. wrote about the interrelatedness the human family. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”[viii]

He stated that “waiting for justice” is rooted in white privilege. “I have never yet engaged in a direct-action movement that was “well timed” according to the timetable of those who have not suffered unduly from the disease of segregation … “wait” has almost always meant “never” … I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say “wait.” … when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodyness” — then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.”[ix]

He addressed the criticism that the campaign involved breaking laws. “‘How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?’ The answer is found in the fact that there are two types of laws: there are just laws, and there are unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that ‘An unjust law is no law at all.’”[x]

He confessed his disappointment with white moderates who encouraged waiting and moving slowly. He directed specific criticisms at the church. “I have heard numerous religious leaders of the South call upon their worshipers to comply with a desegregation decision because it is the law, but I have longed to hear white ministers say, follow this decree because integration is morally right … I have watched white churches stand on the sidelines and merely mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities.”[xi] “Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s often vocal sanction of things as they are.”[xii]

The Letter from Birmingham City Jail notes that we are not destined to choose either to accommodate injustice or to resort to violence. There is a third way. The nonviolent way of Jesus. The letter provides a succinct and profound description of the theology and principles of nonviolent resistance.

The Rev. Dr. King, Jr. wrote out of love inviting his readers to join that “long and bitter — but beautiful — struggle for a new world”.[xiii] Addressed to eight white clergymen, the vision and the criticisms of the letter speak to the white community and the church in all times.

June 20, 2018. St. Louis, Missouri.

The 223rd General Assembly (2018) of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) voted to commend the “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” for study as a resource that provides prophetic witness that inspires, challenges, and educates both church and world. The Assembly also voted to begin the process to include the Letter in the Book of Confessions which is part of the constitution of our church.[xiv]

The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) affirms multiple creeds and confessions that declare “to its members and to the world who and what it is, what it believes, and what it resolves to do.”[xv] Our creeds and confessions “arose in response to particular circumstances within the history of God’s people. They claim the truth of the Gospel at those points where their authors perceived that truth to be at risk. They are the result of prayer, thought, and experience within a living tradition. They appeal to the universal truth of the Gospel while expressing that truth within the social and cultural assumptions of their time. They affirm a common faith tradition, while also from time to time standing in tension with each other.”[xvi]

Should the Letter from Birmingham City Jail be added to the Book of Confessions, it would help shape and guide our church. The Letter from Birmingham City Jail would be one of the confessions that we agree will instruct and lead us in our ordination vows.[xvii]

January 21, 2019. The Bronx, New York.

How does this happen? What is the process that the 223rd General Assembly initiated?

We are Presbyterians. It starts with a committee.

The Office of the General Assembly appoints a study committee to consider the proposal. It consists of ruling elders and ministers of the Word and Sacrament with representation coming based on synods. That committee is currently being formed. If you would have interest in serving, let me know and I can help you make the appropriate connection.

That committee will report to the next General Assembly which meets in 2020 in Baltimore. That Assembly considers and votes on the committee’s report. If the Assembly votes to include the Letter from Birmingham Jail, it would send a proposed amendment to the presbyteries for a vote. If two-thirds of the presbyteries approve the amendment, then the General Assembly meeting in 2022 in Columbus, Ohio would confirm that action and the letter would be added to the Book of Confessions.

That’s a long process. It’s decent. It’s orderly. And in some ways, it is a form of ecclesiastical waiting.

But church, while we wait for the General Assembly’s action, we do not have to wait to put the words of the Letter from Birmingham Jail into action. The General Assembly has commended the letter to us for study and as a prophetic witness to inspire, challenge, and educate ourselves and the church and the world.

We can use the letter now to become, in a word from the letter, extremists. Extremists like Jesus. And the prophets. And Mrs. Rosa Parks. And the Rev. Dr. King, Jr. And so many others. Extremists for love. Extremists for justice. May it be so. May we be so. Amen.[xviii]

[i] https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/boutwell-albert

[ii] https://www.pc-biz.org/#/search/3000321

[iii] https://www.pc-biz.org/#/search/3000321

[iv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birmingham_campaign#Conflict_escalation

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_from_Birmingham_Jail

[vi] https://www.pc-biz.org/#/search/3000321

[vii] https://www.pc-biz.org/#/search/3000321

[viii] https://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/documents/Letter_Birmingham_Jail.pdf

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/US_History_reader/Chapter14/MLKriverside.htm

[xiv] https://pcbiz.s3.amazonaws.com/Uploads/e20a08ef-0d69-4099-985b-f3bc5440f560/Plenary_V_GA_2018_Minutes_1.pdf

[xv] Book of Order, F-2.01 The Purpose of Confessional Statements

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Book of Order, W-4.0404c

[xviii] https://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/documents/Letter_Birmingham_Jail.pdf

We honor the memory of Andy Henriquez, 19 years old. He begged for medical attention in solitary confinement on Rikers Island. He died there due to neglect in 2013.

We honor the memory of Andy Henriquez, 19 years old. He begged for medical attention in solitary confinement on Rikers Island. He died there due to neglect in 2013.